Anti-Catholicism was present in America since its founding though, by the early 19th century it had become “largely rhetorical.” The influx of Catholic immigrants, however, as well as the increasingly aggressive and authoritarian stance of the papacy, which became more outspoken in its denunciations of modernism and liberalism, established a fear that Catholics posed a genuine threat. Conspiracy theories of a papal takeover of the United States abounded.

Anti-Catholicism was present in America since its founding though, by the early 19th century it had become “largely rhetorical.” The influx of Catholic immigrants, however, as well as the increasingly aggressive and authoritarian stance of the papacy, which became more outspoken in its denunciations of modernism and liberalism, established a fear that Catholics posed a genuine threat. Conspiracy theories of a papal takeover of the United States abounded.

A large dimension of the Protestant revival that began in the late 1820s included militant attacks against the Catholic Church which claimed that the Catholic religion was threatening to America’s Protestant culture. Nativists and evangelicals characterized Catholicism as an authoritative religion incompatible with republicanism. Viewed as submissive and unquestioning followers, those of Catholic faith were seen as lacking the individuality and free thinking required of democratic citizens. Moreover, the Catholic immigrant, whose allegiance was to a foreign ruler, was seen as disloyal to America.

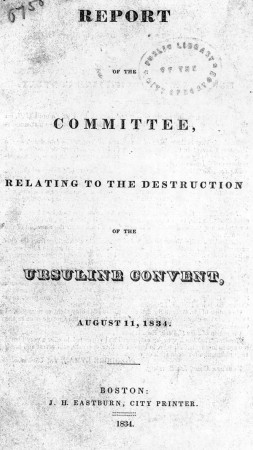

Anti-Catholic sentiments led to violence in the summer of 1834. Sparked by rumors that nuns were being kept against their will, a mob attacked and burnt to the ground an Ursuline convent and school (attended mostly by the daughters of wealthy Protestants) in Charlestown, Massachusetts. Fortunately, no one was killed.

Philadelphia became one of the centers of anti-Catholic protest, second only to Hartford Connecticut in the amount of anti-Catholic materials published. The trustee problems that plagued Philadelphia beginning in the 1820s played a significant role, badly damaging the reputation of Catholics and left Philadelphians suspicious of the motives of the Catholic hierarchy.

In this pamphlet published in Philadelphia in 1833, Samuel Smith, a former priest, discusses what he sees as significant problems with the Catholic Church

Trusteeism involved the practice of Catholic laity assuming control of the administration of churches, even to the point of hiring and firing pastors. This practice began in colonial times when laymen raised money, purchased land, and built churches themselves due to the decentralized structure of the early Church. Bishops’ rejection of such lay involvement caused frequent confrontations and denunciations that often led to the interdiction of churches. The trustees’ presentation of themselves as defenders of democratic rights against autocratic authority of the bishop bolstered Protestant beliefs that the Catholic Church was incompatible with American values.

In 1842, the American Protestant Association was formed in Philadelphia by more than 50 Protestant clergymen from every denomination. The APA’s objective was to alert the public, through lectures, publications, and revivals, to the dangers of popery, or “romanism.” The association gained attention through a series of popular lectures, especially those by the ex-priest Reverend William Hogan, who spread incredible lies about the Catholic Church after leaving it.

Heated debates between Catholic and Protestant clergymen occurred in Philadelphia during the 1830s. One of the most well-known were the exchanges between John Breckinridge, secretary and general agent of the Board of Education of the Presbyterian Church and John Hughes, pastor of St. John the Evangelist Church, who later gained notoriety as bishop of New York.

As a way to present his side of the argument, Hughes started The Catholic Herald, the first long lived diocesan paper in Philadelphia. The newspaper would become the mouthpiece for Bishop Kenrick’s campaign to end Protestant proselytizing in public schools.

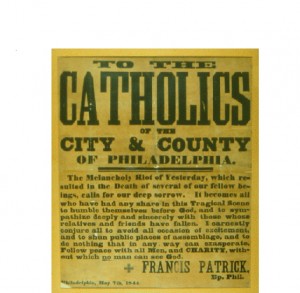

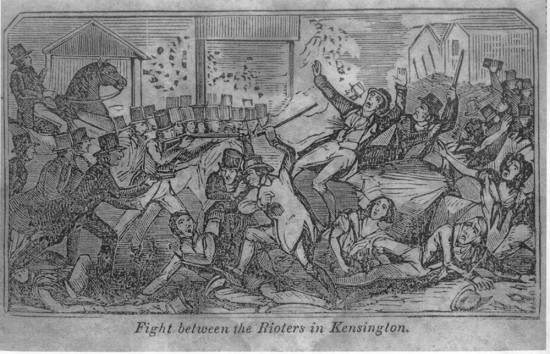

The nativist riots that occurred in the city of Philadelphia in the spring and summer of 1844 were the culmination of anti-Catholic sentiments and the growing nativist movement in the city. Sparked by the fiercely-contested issue of the presence of the Bible in public schools, the riots resulted in at least 20 deaths and more than 100 injuries. The Irish neighborhood of Kensington was practically destroyed and two churches and a convent were burnt to the ground.

Engraving of the "Rioters in Kensington" from A Full and Complete Account of the Late Awful Riots in Philadelphia Philadelphia: John B. Perry, 1844

The 1844 riots shaped both the growth and development of the city of Philadelphia as well as Catholicism in Philadelphia. They led to the consolidation of the city and county of Philadelphia and the establishment of an organized police force. Moreover, the riots resulted in the creation of a distinct Catholic subculture in which the Catholic population would establish its own network of parishes, schools, and social service institutions as a haven from a hostile Protestant culture.

References: Feldberg, Michael. The Philadelphia Riots of 1844: A Study of Ethnic Conflict. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1975; O'Toole, James M. The Faithful: A History of Catholics in America. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008; Archdiocese of Philadelphia. Our faith-filled heritage : The church of Philadelphia bicentennial as a diocese 1808-2008. Strasbourg : Editions du Signe, 2007.

PAHRC has a significant number of 19th-century pamphlets in its General Pamphlet Collection. The Archives also has an almost complete run of official Philadelphia Diocesan newspapers up to the current Archdiocesan paper, The Catholic Standard and Times. More information on the riots can be found in the Nativist Riots of 1844 Papers.