With this month being Irish History Month, we want to share a story that belongs to both Irish and American history: the story of Duffy’s Cut. Being an alumnus of Immaculata University and a member of the Duffy's Cut dig crew, this story is part of my history.

The early years of the United States were not the most hospitable to those of Irish descent, even though several Irishmen were essential in helping create the new nation, such as Thomas Fitzsimmons and Commodore John Barry. Ireland, under British rule, was not the best place for Catholics. Protestants got the better jobs, while Catholics were poorly treated, often not allowed to hold public office and forced to work for absentee British landlords. The prospect of America and a fresh start to life were in the minds of many Irish Catholics. Though the sectarian divide was present in America as it was in Ireland, the Industrial Revolution in America was more willing to give them jobs on improvement projects like the Philadelphia and Columbus Railroad. For these new immigrants, organizations like the Friendly Sons of Saint Patrick for the Relief of Immigrants would assist them in finding jobs in and around Philadelphia.

Philadelphia and Columbia horsecar near Duffy's Cut, 1832. From Watkin's History of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, 1896

The men and women who worked at Duffy’s Cut arrived from Londonderry in the summer of 1832 on the barque John Stamp. The majority were from Donegal, while others were from Tyrone and Derry. They were met by Philip Duffy, a fellow Irishman who had emigrated to Philadelphia in 1798. Philip Duffy had been working on several sections of the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, and his current contract was Mile 59, one of the most challenging stretches of the route. Riding out to Malvern, the new laborers set up camp and began to work. Cholera, a disease which has been running rampart through the Western world, had reached the camp. Fearful of contracting the disease, along with the added prejudice against Irish Catholics, Duffy did not allow the laborers to leave the camp. A few weeks after arriving in America hoping for a better life, were all dead. Newspapers reported that cholera was to blame, though changing the number from 57 workers to about 8 or 9. Though commemorated and remembered by a few, which is indicated by a stone wall built in 1909, the story lay buried and forgotten.

1909 stone wall built by Martin Clement, future president of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, using track ballast from the old rail line

Years later, in 2002, Rev. J. Francis Watson, pastor of Christ Lutheran Church, found an old Pennsylvania Railroad file among the possessions of their grandfather, Joseph Tripician. The file talked about the deaths of a group of laborers in 1832 in Malvern, and typed on the front was “This file is not desired to leave the office.” He then shared the file with his brother William, a professor of History at Immaculata University. Along with fellow professor John Athes and then-student Earl Schandelmeier, the Watson brothers sought to uncover the story of the laborers. After finding evidence of the shanty and several physical objects (work tools and pipe stems) in 2005, the search for the remains began. With the help of ground-penetrating radar, the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania and a handful of students from Immaculata University, the first remains were found in March of 2009. The reains of six more were found between this point and February of 2012 and, contrary to the newspapers, cholera was not the only culprit. There was evidence of blunt force trauma and bullet wounds, so it was clear to everyone that these laborers were victims of violence, whether due to sectarianism or the fear of spreading cholera.

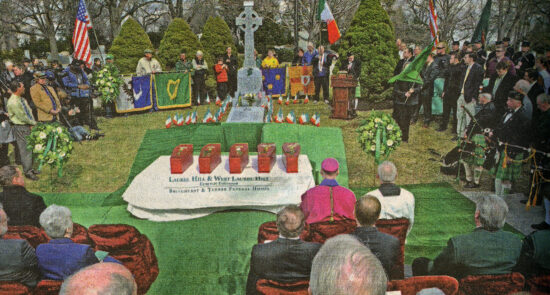

Interment of five sets of remains recovered at Duffy's Cut, West Laurel Hill Cemetery, March 9, 2012

On March 9, 2012, a memorial service was held at West Laurel Hill Cemetery, where the skeletal remains of five of the workers were interred. It was attended by members of the Duffy’s Cut Project, dignitaries of both the United States and Ireland, and the public. In his remarks, Auxiliary Bishop Michael Fitzgerald reminded attendees that each person is created in God’s image and “Although these Irish immigrants were deprived of their human rights in this world, they are not forgotten by God, and we pray that they are at peace in his kingdom.” A few years later, in 2013 and 2015, the remains of two were re-interred back home in Ireland. Through examinations in the skeletal remains and DNA evidence, these remains were identified as John Ruddy and Catherine Burns. It is suspected that the remains of the other 50 lie in a mass grave under the current Paoli-Thorndale line.

In their latest book Massacre at Duffy’s Cut, the Watson brothers talk about how the incident at Duffy’s Cut was not a localized case, and that around “twenty thousand Irish immigrant laborers died in industrial projects on railroads and canals throughout the eastern portion of the United States in the 1820s and 1830s from the Erie Canal to the New Orleans Canal.” They ended the book in saying, “The fifty-seven Irish victims at Duffy’s Cut died building something of great consequence, and trains still pass over the place where they worked and died building Pennsylvania’s pioneering railroad.”

An earlier blog, written in 2010, talks about cholera and its impact within Philadelphia: https://chrc-phila.org/1832-cholera-outbreak-in-philadelphia-and-duffys-cut/