In the last blog post, Nast’s anti-Irish cartoons were examined, revealing beliefs that the Irish were inferior and unable to handle American liberty. This made the Irish a threat to the United States and thus a focus of Nast’s criticism. Connected to this anti-Irish sentiment was also a strong Anti-Catholic feeling throughout the county. Thomas Nast’s cartoons dealt with Anti-Catholicism in two different ways, the first focused on the menace of the pope and the second dealt with the threat to the public school system.

"'The Promised Land,' as seen from the Dome of St. Peter's, Rome" https://omeka.chrc-phila.org/items/show/7354

One of themes conveyed through Nast’s cartoons was that the pope was looking to rule the United States by converting its people to Catholicism. This could be seen in his cartoon drawn in 1870 where the pope and other clergy stand atop St. Peters Basilica and greedily eye America as the promise land. Furthermore, with the inclusion of the weapons in the background, it is clear that Nast is suggesting that unless America is vigilant, it risks conquest by the papacy. This perceived threat of Rome is seen elsewhere in Nast's work, such as with a cartoon showing Uncle Sam offering to free an American Catholic priest from the Pope's plans to rule both church and state. This is an important cartoon since it suggests that the problem with Catholics is not their faith but rather their allegiance to a foreign power, and thus if Catholics removed that, then they would be acceptable.

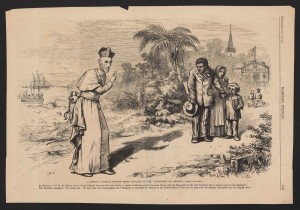

"A Roman Catholic Mission from England to the "heathens" of America" https://omeka.chrc-phila.org/items/show/7358

In addition to anti-papal sentiment, Nast seems to question the merit of Catholicism on a whole in another cartoon where he drew a Catholic priest trying convert a recently freed African-American family. However, behind his back the priest holds a pair of shackles, implying that through Catholicism the family will be enslaved again. It is also interesting to note, that in the background is a public school which the family was heading towards, which directly connects into Nast’s other theme that education is the way to fight Catholic enslavement. Through these three cartoons, Nast demonstrated the idea that the pope, by having authority over American Catholics, was a threat to the United States government and its people.

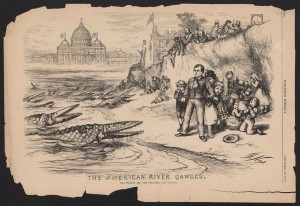

"The American River Ganges. The priests and the children" https://omeka.chrc-phila.org/items/show/7357

Another reason for Nast’s anti-Catholic drawings was a fear that Catholics were attacking the public school system, which Nast saw as integral to the foundation of the United States.[1] The reason Nast and others were concerned over the public school system was at this time Catholics were protesting the use of Protestant bibles and prayers at schools and wished to see the practice ended. Furthermore, the rise of parochial schools and some attempts by politicians, most notably Boss Tweed, to use state money to help fund these parochial schools raised concern that these religious institutions would replace the public school system completely.[2] One of Nast’s most famous cartoons, “The American River Ganges,” published in 1871 depicts bishops shaped as crocodiles coming to devour children as a public school lays in ruins. Thus, the cartoon demonstrates a belief that Catholicism by destroying public schools will destroy the future of the country. Additionally, in the background of the cartoon, an image of the Vatican with both the papal and Irish flags flying as well as a building titled “the political Roman Catholic school,” reveal the origins of these threats to America.

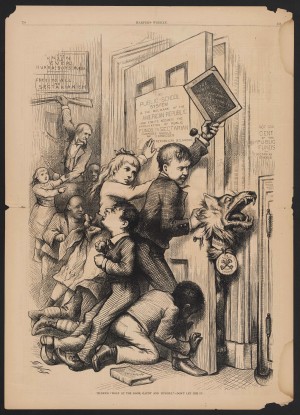

"Tilden's 'Wolf at the Door, Gaunt and Hungry.' Don't let him in" https://omeka.chrc-phila.org/items/show/7367

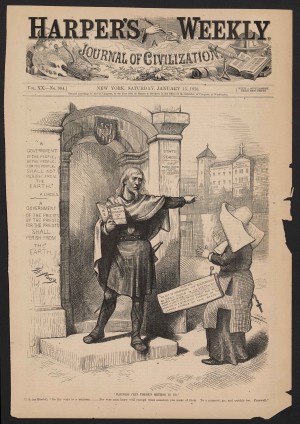

Indeed, Nast was deeply troubled by the Church’s attempt to infiltrate the public school system as seen in two cartoons drawn in 1876. The first depicts a wolf with a papal and Democrat party collar trying to force its way into a school room as the children barricade the door. Nast makes clear that public schools need to be made safe from the Catholic menace since they are the “bulwark of the American Republic.” Indeed, in the background of the cartoon, Uncle Sam can be seen grabbing a gun above a plaque that reads "free for all; no sectarianism,” implying that the only way to protect the schools, and by extension America, is to eliminate the Catholic Church. The second cartoon takes much of its inspiration from Hamlet as Uncle Sam banishes a nun trying to teach at a public school to a convent. An interesting aspect of this cartoon is a parody of a quote by Lincoln that reads “a government of the priests, by the priests, for the priests shall perish from the earth.” This illustrates that Nast believes that Catholicism is incompatible with American democracy and will eventually die out once people are free from the Church. Additionally, Nast’s anti-Catholic sentiment was made even clearer by the use of the Shakespeare quote that the nun, representing the Church, makes monsters out of men. Indeed, when coupled with the phrase, “our public school system must and shall be preserved,” it reveals that Nast saw Catholicism as a threat to the very core of America.

"Madness (Yet there's method in it)" https://omeka.chrc-phila.org/items/show/7363

Thomas Nast’s cartoons from the 1870s expressed his strong anti-Irish and anti-Catholic feelings and his fear these forces would destroy America. With a circulation on average of 100,000 and reaching peaks of 300,000 Harper’s Weekly not only was a vehicle for spreading these sentiments but was also a reflection of its readership’s feelings, since Nast would not have remained widely popular if his audience disagreed with his cartoons.[3] Thus by studying this cartoons one is able to come to a better understanding of the social conflicts and prejudices that existed in America during the late 1800s.

Visit our archives or our digital collections for more historic cartoons.

-

[1] Benjamin Justice, “Thomas Nast and the Public School of the 1870s,” History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Summer, 2005), 180.

-

[2] Ibid., 182.

-

[3] Joshua Brown, Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis of Gilded Age America, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 62; Niall Whelehan, The Dynamiters: Irish Nationalism and Political Violence in the Wider World, 1867–1900, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 225.