Among the recently digitized images added to our online collection are a number of drawings by cartoonist Thomas Nast. In 1846 at the age of six, Nast immigrated with his mother to the United States and by age 15 he had begun drawing for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News.[1] He joined Harper’s Weekly in 1862 and at his height of fame was earning close to $20,000 a year (roughly $500,000 in today’s dollars) drawing for the paper.[2] Studying these cartoons can help us better understand the culture of the United States during the 1870s. Examining cartoons is an important tool because, as historian Thomas Milton Kemnitz asserted, the cartoons’ value rests in what they can “reveal about the societies that produced them.” [3] Once a cartoon is understood within its historical context, it can highlight public opinions that could not be revealed in more traditional written records.[4] Thus, in many ways cartoons are not only an artifact of popular culture but also help to shape and reflect public sentiment. The Thomas Nast cartoons in our collection tell a story of the ingrained anti-Irish and anti-Catholic attitude during the 1870s. Before discussing the content of the cartoons it is important to establish the context of their period. Dating back to the founding of America, there has been fear that immigrants, because of their supposed ignorance, will “fatally depreciate, degrade, and demoralize” the government and culture.[5] Nativism in the United States often took the form of anti-Irish and anti-Catholic feelings as seen in the Nativist Riots in Philadelphia in 1844, which resulted in dozens killed and over a hundred wounded, along with two churches and a convent burned to the ground.[6] These anti-Catholic feelings stemmed from the allegiance of the Irish Catholics, who were seen by many Americans as loyal to the pope over the United States. Indeed, many believed that Catholicism was incompatible with democracy and that it threatened the established Protestant culture in the country.[7]

The Thomas Nast cartoons in our collection tell a story of the ingrained anti-Irish and anti-Catholic attitude during the 1870s. Before discussing the content of the cartoons it is important to establish the context of their period. Dating back to the founding of America, there has been fear that immigrants, because of their supposed ignorance, will “fatally depreciate, degrade, and demoralize” the government and culture.[5] Nativism in the United States often took the form of anti-Irish and anti-Catholic feelings as seen in the Nativist Riots in Philadelphia in 1844, which resulted in dozens killed and over a hundred wounded, along with two churches and a convent burned to the ground.[6] These anti-Catholic feelings stemmed from the allegiance of the Irish Catholics, who were seen by many Americans as loyal to the pope over the United States. Indeed, many believed that Catholicism was incompatible with democracy and that it threatened the established Protestant culture in the country.[7]

“Something that will not "blow over." https://omeka.chrc-phila.org/items/show/7366

Nast’s anti-Irish cartoons focus on the Irish as a destructive and lying group, who endangered American society. In the immediate aftermath of the Orange Riot of July 12, 1871 in New York City, in which Irish Catholics clashed with the National Guard protecting an Irish Protestant parade, Nast drew a number of anti-Irish cartoons for Harper’s Weekly. One cartoon illustrated the Draft Riots of July 1863, where Irish Catholics attacked African-Americans throughout New York City. At the top of the drawing Nast wrote that the Irish Catholic is bound to respect “no caste, no sect, no nation, any rights,” highlighting the believed lack of respect the Irish immigrants had for American society. Furthermore, the contrast between the Irish and the Anglo-Saxons in this cartoon clearly shows the Irish in negative light. While the Anglo-Saxons are drawn as regular looking people, the Irish are drawn with ape-like faces illustrating their inferiority as well as the lack of intelligence. Such depictions of Irish were not limited to Nast, with other papers such as Puck and Judge also using caricatures of Irish as primitive and violent.[8]

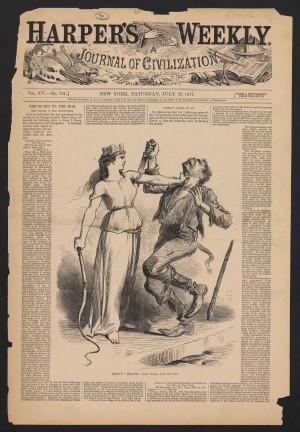

"Bravo, Bravo!" https://omeka.chrc-phila.org/items/show/7356

The other drawing that Nast published on the front cover of Harper’s Weekly in 1871 shows an Irish man with an ape-like face attacking Columbia, a common representation of America. However, Columbia was able to stop the attack and defiantly clutches the Irishman by the neck as he drops his shillelagh. The contrast between the two is clear, the Irishman in his ripped and tattered clothes, with a loose suspender looking not unlike a tail, represented his inhumanity as well as his threat to American society, which was represented by Columbia dressed in pure white and holding a whip labeled “law.”[9] Thus for Nast, the riots that the Irish Catholics were regularly involved in demonstrated clear evidence of their inferiority and justified his concern that they would be a threat to democracy.

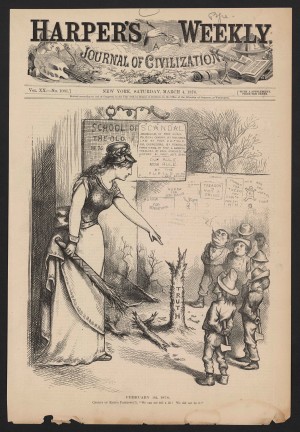

"Chorus of Rising Patriots (?). 'We can not tell a lie! We did not do it!'"https://omeka.chrc-phila.org/items/show/7364

Another cartoon a few years later also illustrates anti-Irish sentiment but in a different way. In this cartoon, a group of children representing Irish Catholic Democrats have cut down the tree of truth and have put up a sign for a new school with the slogan, “our rule, mob rule.” The cartoon further shows them supporting Boss Tweed, the Democrat whose political machine ran New York. Thus by depicting them as children, Nast was questioning their ability to think on their own and their ability to partake in democracy. Another important aspect of this cartoon is Columbia, who this time is dressed as a Greek goddess. Here she holds a bundle of sticks with the phrase “in union there is strength, patriotism, honor, and unity” and is clearly defending the spirit of the Revolution by standing in front of the “school of the old 1776.” Thus, this cartoon along with the other two demonstrate how Nast believed that the ideals that the United States were founded on were in danger because of the treachery of the Irish. Examining Nast’s anti-Irish cartoons has revealed the deep-seated anti-immigrant feelings that were held by many in the United States. Such beliefs were developed in the wake of riots and other violent episodes that many saw as a sign that the Irish were incompatible with the ideals of the nation. Indeed, nativism arose due to the fear that the Irish and other ethnic groups would corrupt the fabric of America. This fear of the Irish was compounded because of their Catholic faith, which faced its own opposition in the United States as expressed by Nast in his cartoons. Next blog will explore part two: Nast’s anti-Catholic cartoons.

-

[1] Fiona Deans Halloran, Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 2-3.

-

[2] Vinson, J. Chal. "Thomas Nast and the American Political Scene." American Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1957): 338 & 340.

-

[3] Thomas Milton Kemnitz, "The Cartoon as a Historical Source." The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 4, no. 1 (1973), 82.

-

[4] Ibid., 92-93.

-

[5] Bill Ong Hing, To Be an American: Cultural Pluralism and the Rhetoric of Assimilation, (New York: NYU Press, 1997), 14.

-

[6] Karla Irwin, “Chaos in the Streets: The Philadelphia Riots of 1844,” Villanova University Falvey Memorial Library, (2011), https://exhibits.library.villanova.edu/chaos-in-the-streets-the-philadelphia-riots-of-1844.

-

[7] Allison O’Mahen Malcom, “Loyal Orangemen and Republican Nativists: Anti-Catholicism and Historical Memory in Canada and the United States, 1837-67,” in The Loyal Atlantic: Remaking the British Atlantic in the Revolutionary Era, eds. Jerry Bannister, Liam Riordan, (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2012), 218.

-

[8] Benjamin Justice, “Thomas Nast and the Public School of the 1870s,” History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Summer, 2005), 177.

-

[9] Michele Walfred, “‘Bravo, Bravo’: Thomas Nast Cover- 29 July, 1871.” Illustrating Chinese Exclusion, https://thomasnastcartoons.com/irish-catholic-cartoons/something-that-will-not-blow-over-29-july-1971/bravo-bravo-thomas-nast-cover-24-july-1871/.