The Influenza pandemic of 1918-1919, also known as the Spanish Flu, is considered one of the worst epidemics in history. Between the spring of 1918 and the summer of 1919, an estimated 50 million deaths worldwide were attributed to the flu, 34 million more than the total casualties of World War I.[1] In the United States, deaths have been estimated around 675,000, with Philadelphia being one of the hardest hit city with between 13,000 and 16,000 flu related deaths. [2]

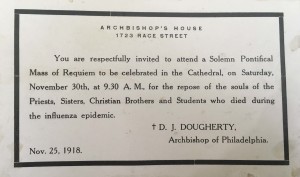

On October 3, 1918, the Board of Health of the city of Philadelphia ordered the closing of all schools and suspended church services until further notice.[3] The ban would remain in effect for most of October, being lifted once the flu ran its course on the 26th.[4] Archbishop Dennis Dougherty offered the use of archdiocesan buildings as temporary hospitals and enlisted all priests, non-cloistered nuns, and the members of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul to aid the victims of the flu.[5] The sisters of numerous religious orders across the city would play an indispensable role in fighting the flu.

Throughout the course of the flu, over 2,000 nuns, about two-thirds of all sisters in the archdiocese, helped care for the sick, functioning mainly as nurses in hospitals across the city.[6] The Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for instance were sent to the Municipal Hospital as well as acted as private nurses, going door to door in poor neighborhoods to find and care for the sick. The sisters who taught as St. Peters Claver’s School helped turn the building into an emergency hospital and served as nurses for the close to 50 patients who would be treated in the building.[7] The Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis also were deeply involved in the fight against the flu as the sisters ran three hospitals, St. Agnes, St. Mary, and St. Joseph, which together saw over 1,300 patients.[8] Other religious orders that sent nurses to various hospitals across the city included Sisters of the Holy Child Jesus, Sisters of the Immaculate Heart, Sisters of Saint Joseph, Sisters of Mercy, and Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur.

An account from an IHM nun recalls entering houses and finding entire families sick in bed together with no one to care for them. When this happened the sisters would bathe the sick, clean the house and then prepare food and medicine for the sick.[9] Sisters working in the hospitals, despite a lack of experience, were tasked with mixing medicines as well as taking temperatures and feeding the sick. Many sisters worked 12 hours shifts, with one stating that “through this experience I have learned to appreciate my vocation to the religious life more than ever before.”[10]

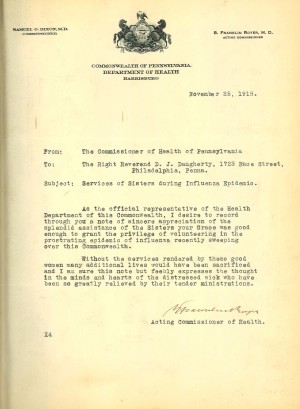

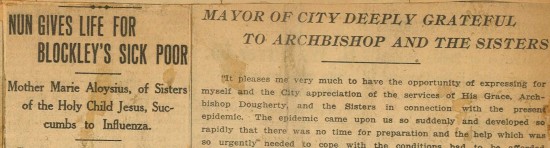

The impact of the sisters’ work was immeasurable as without them many hospitals would have been dangerously understaffed and unable to care for the inflected. Many patients credited the sisters for helping them pull through and the medical staff would comment that they could “see the change there is in this place since the Sisters came.”[11] After the epidemic had subsided, government officials praised the work of the sisters with the Pennsylvania Department of Heath stating that “without the serviced rendered by these good women many additional lives would have been sacrificed.”[12] The mayor of Philadelphia echoed similar sentiment in a letter declaring that “I have never seen a greater demonstration of real charity or self-sacrifice than has been given by the sisters in their nursing of the sick.”[13]

Since the sisters were put into direct contact with the flu when caring for the sick, a number of them would also become infected with the disease. It was recorded that 23 sisters died from the flu. One such case reported in the Catholic Standard and Times stated that Mother Marie Aloysius of the Sisters of the Holy Child Jesus had continued working in the hospital despite her sickness until the day before she passed.[14] The serve and sacrifice of the religious sisters during the Spanish Flu epidemic is an important part of Philadelphia history that must be remembered and celebrated. Indeed, their largely anonymous actions helped save the lives of many throughout the city and keep the worst pandemic from being even more deadly.

For more information on the Spanish Flu and the archdiocese's response visit our digital exhibit "The Spanish Lady in the City of Brotherly Love: The Archdiocese of Philadelphia and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919."

-

[1] “The Deadly Virus: The Influenza Epidemic in 1918,” National Archives and Records Administration, https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/influenza-epidemic/.

-

[2] “1918 Flu Pandemic,” History, (2010), http://www.history.com/topics/1918-flu-pandemic; “1918 Influenza Epidemic Records,” Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission, http://www.phmc.pa.gov/Archives/Research-Online/Pages/1918-Influenza-Epidemic.aspx.

-

[3] Letter from Archbishop Dougherty dated Oct 4th 1918. SB-10, April 7, 1917- Feb. 12, 1920, Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

-

[4] Letter from Rodgers, secretary of the board of health, Oct. 25, 1918. SB-10, April 7, 1917- Feb. 12, 1920, Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

-

[5] “His Grace Gives Instant Aid to City Fighting Epidemic,” Catholic Standard and Times, October 12, 1918. SB-10, April 7, 1917- Feb. 12, 1920, Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

-

[6] “Unparalleled in history of city,” undated. SB-10, April 7, 1917- Feb. 12, 1920, Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

-

[7] Francis Edward Tourscher, Work of the Sisters during the epidemic of influenza, October, 1918, (Philadelphia: American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, 1919), 3-6.

-

[8] Ibid., 7.

-

[9] Ibid., 21.

-

[10] Ibid., 24.

-

[11] Ibid., 26 & 31.

-

[12] Letter from Commissioner of Health of Pennsylvania to the Right Reverbed Dougherty on November 25, 1918. SB-10, April 7, 1917- Feb. 12, 1920, Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

-

[13] “Mayor of City Deeply Grateful to Archbishop and the Sisters,” The Catholic Standard and Times, October 19, 1918. SB-10, April 7, 1917- Feb. 12, 1920 Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

-

[14] “Nun Gives Life for Blockley’s Sick Poor,” The Catholic Standard and Times, October 19, 1918. SB-10, April 7, 1917- Feb. 12, 1920, Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.