In the summer of 1926, Philadelphia set out to remind the nation where it all began. To mark the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the city hosted the Sesquicentennial International Exposition, a massive world’s fair intended to celebrate American progress, industry, and culture. For months, Philadelphia transformed itself into a spectacle of pageantry and ambition—yet today, the exposition is one of the city’s most overlooked historical moments.

The undeveloped land that the Sesquicentennial Exposition was to be built on in South Philadelphia. https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/50124

Talks of having a second World’s Fair in Philadelphia began around 1876 with John Wanamaker, the department store magnate, suggesting it should take place in 1926, coinciding with America’s 150th anniversary. This was not the first time that Philadelphia hosted a World's Fair, as the City was home to the Centennial Exposition just 50 years before in 1876. Planning began in 1916, and the Fair was to be centered on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and Fairmount Park, but the entry of the United States into World War I paused all plans. By the time the war ended, the country was dealing with the Spanish Flu and plans fell once again with the death of John Wanamaker in 1922. Plans resumed in 1924 when the newly-elected mayor of Philadelphia, W. Freeland Kendrick, made the decision to abandon the Parkway/Fairmount location and move the Exposition to South Philadelphia below Oregon Avenue. At the time, this area was undeveloped swampland, but City officials saw it as an opportunity to stimulate long-term economic growth, real estate development, and infrastructure improvements.

The Liberty Bell archway at night, looking north on Broad Street. https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/50710

The Sesquicentennial Exposition opened up on June 1st, and lasted until November 30th. It was filled with many different features. Upon entering the Fair, visitors were met with an 80-foot illuminated replica of the Liberty Bell, adorned with 26,000 light bulbs, which would be at today’s Marconi Park. There were exhibition halls dedicated to showcasing new products and industries, amusement rides, and pavilions hosted by different countries from around the world. One of the features of the Exposition was a recreation of High Street, showcasing buildings and life in Colonial Philadelphia. However, there were many aspects that made the event lackluster. During the 184 days that the Exposition was open, spectators were met with rain on 107 of the days. Though the Fair opened in the beginning of June, many of the buildings with not finished in time, while some did not even get built due to lack of funds. Both of these stemmed from construction only starting a year before the Fair’s opening.

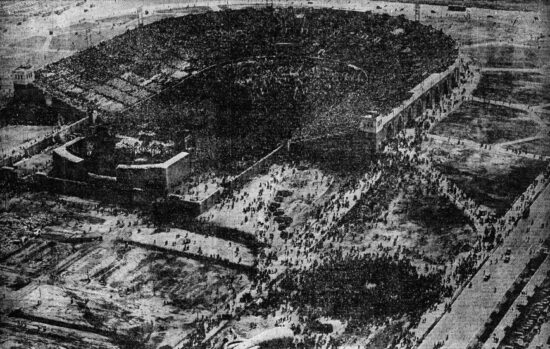

Some of the 140,000 spectators at the Sesquicentennial Stadium, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 23 September 1926 for the Jack Dempsey vs. Gene Tunney match.

Two of the largest events of the Fair took place at Municipal Stadium, which many would know as the demolished John F. Kennedy Stadium, just a little over a week apart. The first was a boxing match where Jack Dempsey lost his heavyweight boxing title to Gene Tunney. Over 120,000 spectators packed the stadium in the rain on the evening of September 23rd. Despite the downfalls of the Sesquicentennial Exposition, it was reported that “not only did Gene Tunney win in the rain-soaked affair, but Philadelphia and the Sesquicentennial won also, in money and prestige alike.” [1] It was estimated that 3 to 5 million dollars were added to the City’s money reserves.

The second event was the Solemn Pontifical Mass. Presided over by Cardinal Dennis Dougherty, the Mass drew an estimated 300,000 Catholics, making it one of the largest religious gatherings in the city’s history at the time. To accommodate the amount of people who could not fit inside, additional altars were set up outside the stadium. The ceremony featured an altar modeled after that of Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome and “stressed the contribution of the Church to the liberation of man and in particular the contribution of Catholics to the freedom and prosperity of the United States.” [2] With these two events, September and October the most attended months of the Exposition.

Aerial view of the Solemn Pontifical Mass. The Catholic Standard and Times, Volume 31, Number 49, 9 October 1926

Like the Centennial Exposition, not much exists from the Sesquicentennial Exposition. Until 1992, John F. Kennedy Stadium continued to host many outdoor events, such as Cardinal Dougherty’s Golden Jubilee Mass in 1941, and the full-day concert Live Aid in 1985. The only surviving structure resides in FDR Park: the American Swedish Historical Museum, originally called the John Hanson–John Morton Memorial Building. Much like its modern counterpart, it was devoted to the preservation of achievements in America by citizens of Swedish descent. The second structure is the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, which opened on July 1, 1926, connecting Philadelphia to New Jersey for the first time. Originally known as the Delaware River Bridge, it was the longest suspension bridge in the world until 1929.

[1] Keels, Thomas H., Sesqui: Greed, Graft, and the Forgotten World's Fair of 1926. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017, 254

[2] Connelly, James F. The History of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. Wynnewood: Unigraphics Inc., 1976, 374